Maslow's hierarchy of needs

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is a theory in psychology, proposed by Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper "A Theory of Human Motivation."[2] Maslow subsequently extended the idea to include his observations of humans' innate curiosity. His theories parallel many other theories of human developmental psychology, all of which focus on describing the stages of growth in humans. Maslow use the terms Physiological, Safety, Belongingness and Love, Esteem, and Self-Actualization needs to describe the pattern that human motivations generally move through.

Maslow studied what he called exemplary people such as Albert Einstein, Jane Addams, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Frederick Douglass rather than mentally ill or neurotic people, writing that "the study of crippled, stunted, immature, and unhealthy specimens can yield only a cripple psychology and a cripple philosophy."[3] Maslow studied the healthiest 1% of the college student population.[4]

Maslow's theory was fully expressed in his 1954 book Motivation and Personality.[5]

Contents |

Hierarchy

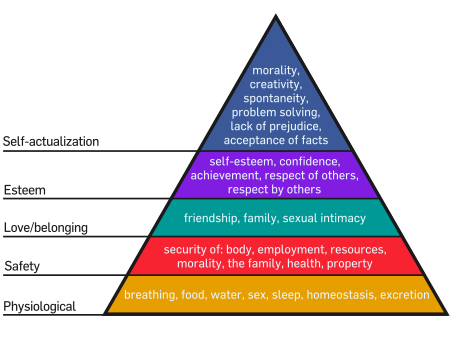

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is often portrayed in the shape of a pyramid, with the largest and most fundamental levels of needs at the bottom, and the need for self-actualization at the top.[1][6] While the pyramid has become the de facto way to represent the hierarchy, Maslow himself never used a pyramid to describe these levels in any of his writings on the subject.

The most fundamental and basic four layers of the pyramid contain what Maslow called "deficiency needs" or "d-needs": esteem, friendship and love, security, and physical needs. With the exception of the most fundamental (physiological) needs, if these "deficiency needs" are not met, the body gives no physical indication but the individual feels anxious and tense. Maslow's theory suggests that the most basic level of needs must be met before the individual will strongly desire (or focus motivation upon) the secondary or higher level needs. Maslow also coined the term Metamotivation to describe the motivation of people who go beyond the scope of the basic needs and strive for constant betterment.[7] Metamotivated people are driven by B-needs (Being Needs), instead of deficiency needs (D-Needs).

The human mind and brain are complex and have parallel processes running at the same time, so many different motivations from different levels of Maslow's pyramid usually occur at the same time. Maslow was clear about speaking of these levels and their satisfaction in terms such as "relative" and "general" and "primarily", and says that the human organism is "dominated" by a certain need[8], rather than saying that the individual is "only" focused on a certain need at any given time. So Maslow acknowledges that many different levels of motivation are likely to be going on in a human all at once. His focus in discussing the hierarchy was to identify the basic types of motivations, and the order that they generally progress as lower needs are reasonably well met.

Physiological needs

For the most part, physiological needs are obvious – they are the literal requirements for human survival. If these requirements are not met, the human body simply cannot continue to function.

Physiological needs are the most prepotent of all the other needs. Therefore, the human that lacks food, love, esteem, or safety would consider the greatest of his/her needs to be food.

Air, water, and food are metabolic requirements for survival in all animals, including humans. Clothing and shelter provide necessary protection from the elements. The intensity of the human sexual instinct is shaped more by sexual competition than maintaining a birth rate adequate to survival of the species.

Safety needs

With their physical needs relatively satisfied, the individual's safety needs take precedence and dominate behavior. In the absence of physical safety – due to war, natural disaster, or, in cases of family violence, childhood abuse, etc. – people (re-)experience post-traumatic stress disorder and trans-generational trauma transfer. In the absence of economic safety – due to economic crisis and lack of work opportunities – these safety needs manifest themselves in such things as a preference for job security, grievance procedures for protecting the individual from unilateral authority, savings accounts, insurance policies, reasonable disability accommodations, and the like. This level is more likely to be found in children because they have a greater need to feel safe.

Safety and Security needs include:

- Personal security

- Financial security

- Health and well-being

- Safety net against accidents/illness and their adverse impacts

Love and belonging

After physiological and safety needs are fulfilled, the third layer of human needs are interpersonal and involve feelings of belongingness. The need is especially strong in childhood and can over-ride the need for safety as witnessed in children who cling to abusive parents. Deficiencies with respect to this aspect of Maslow's hierarchy – due to hospitalism, neglect, shunning, ostracism etc. – can impact individual's ability to form and maintain emotionally significant relationships in general, such as:

- Friendship

- Intimacy

- Family

Humans need to feel a sense of belonging and acceptance, whether it comes from a large social group, such as clubs, office culture, religious groups, professional organizations, sports teams, gangs, or small social connections (family members, intimate partners, mentors, close colleagues, confidants). They need to love and be loved (sexually and non-sexually) by others. In the absence of these elements, many people become susceptible to loneliness, social anxiety, and clinical depression. This need for belonging can often overcome the physiological and security needs, depending on the strength of the peer pressure; an anorexic, for example, may ignore the need to eat and the security of health for a feeling of control and belonging.[citation needed]

Esteem

All humans have a need to be respected and to have self-esteem and self-respect. Esteem presents the normal human desire to be accepted and valued by others. People need to engage themselves to gain recognition and have an activity or activities that give the person a sense of contribution, to feel self-valued, be it in a profession or hobby. Imbalances at this level can result in low self-esteem or an inferiority complex. People with low self-esteem need respect from others. They may seek fame or glory, which again depends on others. Note, however, that many people with low self-esteem will not be able to improve their view of themselves simply by receiving fame, respect, and glory externally, but must first accept themselves internally. Psychological imbalances such as depression can also prevent one from obtaining self-esteem on both levels.

Most people have a need for a stable self-respect and self-esteem. Maslow noted two versions of esteem needs, a lower one and a higher one. The lower one is the need for the respect of others, the need for status, recognition, fame, prestige, and attention. The higher one is the need for self-respect, the need for strength, competence, mastery, self-confidence, independence and freedom. The latter one ranks higher because it rests more on inner competence won through experience. Deprivation of these needs can lead to an inferiority complex, weakness and helplessness.

Maslow also states that even though these are examples of how the quest for knowledge is separate from basic needs he warns that these “two hierarchies are interrelated rather than sharply separated” (Maslow 97). This means that this level of need, as well as the next and highest level, are not strict, separate levels but closely related to others, and this is possibly the reason that these two levels of need are left out of most textbooks.

Self-actualization

“What a man can be, he must be.”[9] This forms the basis of the perceived need for self-actualization. This level of need pertains to what a person's full potential is and realizing that potential. Maslow describes this desire as the desire to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming.[10] This is a broad definition of the need for self-actualization, but when applied to individuals the need is specific. For example one individual may have the strong desire to become an ideal parent, in another it may be expressed athletically, and in another it may be expressed in painting, pictures, or inventions.[11] As mentioned before, in order to reach a clear understanding of this level of need one must first not only achieve the previous needs, physiological, safety, love, and esteem, but master these needs.

Self-transcendence

Viktor Frankl later added Self-transcendence [12][better source needed] to create his own version of Maslow's Hierarchy. Cloninger later incorporated self-transcendence as a spiritual dimension of personality in the Temperament and Character Inventory.[13]

Research

Recent research appears to validate the existence of universal human needs, although the hierarchy proposed by Maslow is called into question. [14] [15]

Other research indicates that Maslow's explanations of the hierarchy of human motivation reflects a binary pattern of growth as seen in math. The individual's awareness of first, second, and third person perspectives, and of each one's input needs and output needs, moves through a general pattern that is basically the same as Maslow's described pattern.[16]

Criticisms

In their extensive review of research based on Maslow's theory, Wahba and Brudwell found little evidence for the ranking of needs Maslow described, or even for the existence of a definite hierarchy at all.[17] Chilean economist and philosopher Manfred Max-Neef has also argued fundamental human needs are non-hierarchical, and are ontologically universal and invariant in nature—part of the condition of being human; poverty, he argues, may result from any one of these needs being frustrated, denied or unfulfilled.[citation needed]

The order in which the hierarchy is arranged (with self-actualization as the highest order need) has been criticised as being ethnocentric by Geert Hofstede.[18] Hofstede's criticism of Maslow's pyramid as ethnocentric may stem from the fact that Maslow’s hierarchy of needs neglects to illustrate and expand upon the difference between the social and intellectual needs of those raised in individualistic societies and those raised in collectivist societies. Maslow created his hierarchy of needs from an individualistic perspective, being that he was from the United States, a highly individualistic nation. The needs and drives of those in individualistic societies tend to be more self-centered than those in collectivist societies, focusing on improvement of the self, with self actualization being the apex of self improvement. Since the hierarchy was written from the perspective of an individualist, the order of needs in the hierarchy with self actualization at the top is not representative of the needs of those in collectivist cultures. In collectivist societies, the needs of acceptance and community will outweigh the needs for freedom and individuality.[19]

Some of these criticisms may be really about Maslow's choice of terminology, especially with the term "self-actualization". "Self-actualization" might not effectively convey his observations that this higher level of motivation is really about focusing on becoming the best person one can possibly become, in the service of both the self and others: "A musician must make music, an artist must paint, a poet must write, if he is to be ultimately at peace with himself. What a man can be, he must be. He must be true to his own nature. This need we may call self-actualization."[20] At these higher levels of motivation, what we do generally benefits everyone, but Maslow's term might not be as good at clarifying that as it could have been.

Maslow's hierarchy has also been criticized as being individualistic because of the position and value of sex on the pyramid. Maslow’s pyramid puts sex on the bottom rung of physiological needs, along with breathing and food. It views sex from an individualistic and not collectivist perspective: i.e., as an individualistic physiological need that must be satisfied before one moves on to higher pursuits. This view of sex neglects the emotional, familial and evolutionary implications of sex within the community.[21][22]

Changes to the hierarchy by circumstance

The higher-order (self-esteem and self-actualization) and lower-order (physiological, safety, and love) needs classification of Maslow's hierarchy of needs is not universal and may vary across cultures due to individual differences and available resources in the region or geopolitical entity/country.

Researchers challenged Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory, the higher-order (self-esteem and self-actualization) and lower-order (physiological, safety, and love) classification of the needs, in particular and explored the levels of needs for importance and satisfaction during peacetime and wartime across cultures during and after the first Persian Gulf War. First of all, regarding the importance of needs, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of a 13-item scale showed that there were two levels of needs during real peacetime (1993–94) in the US: survival (physiological and safety) and psychological (love, self-esteem, and self-actualization) needs. The retrospective peacetime measure was established and collected during the Persian Gulf War in 1991 when people in the US were asked to recall the importance of needs one year ago in 1990. Again, only two levels of needs were identified. Therefore, people do have the ability and competence to recall and estimate the importance of needs retrospectively. In addition, two levels of needs regarding satisfaction during peacetime in the US also emerged. In short, there are two levels of needs regarding importance and satisfaction during peacetime in the US.

However, these two levels of needs were different from that of Maslow's model: Social needs were associated with self-esteem and self-actualization (psychological needs).

Second, for citizens in the Middle East (Egypt and Saudi Arabia), there were three levels of needs during retrospective peacetime (1990) regarding importance and satisfaction. These three levels were completely different from those individuals in the US. For example, due to significant differences in natural resources across countries, during peacetime, water was the least important need for people in the US, but was the most important need for those in the Middle East. Third, changes regarding the importance and satisfaction of needs from the retrospective peacetime to the wartime due to stress varied significantly across cultures (the US vs. Middle East). For people in the US, there was only one level of needs regarding the importance of needs during the war because due to stress, people considered all needs equally important. For example, the most significant increase regarding the importance of needs from peacetime to wartime was the security and safety of the country because people have taken that (the safety of the country) for granted during peacetime. Regarding satisfaction of needs during the war in the US, there were three levels: (1) physiological needs, (2) safety needs, and (3) the psychological needs (social, self-esteem, self-actualization).

The satisfaction of physiological needs and safety needs (combined as one during peacetime) were separated into two independent needs during the war. For people in the Middle East, the satisfaction of needs changed from three levels during peacetime to two levels during the war. It is also interesting to note that self-esteem was the least satisfied needs for people in the US and in the Middle East, a rare, common finding. [23][24][25] The importance and satisfaction of people’s needs were different across cultures and the changes of human needs from peacetime to wartime did vary across cultures. Therefore, human needs are unique, dynamic, and changing.

See also

- ERG theory, which further expands and explains Maslow's theory

- Fundamental human needs, Manfred Max-Neef's model

- John Curtis Gowan

- Metamotivation

- Murray's psychogenic needs

- Juan Antonio Pérez López, spontaneous and rational motivation

- Heylighen, Francis. (1992). A cognitive-systemic reconstruction of Maslow’s theory of self-actualization. Behavioral Science, 37(1), 39–58. doi:10.1002/bs.3830370105

References

- ^ a b Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

- ^ Maslow, A.H. (1943). "A Theory of Human Motivation," Psychological Review 50(4): 370-96.

- ^ Maslow, Abraham (1954). Motivation and Personality. New York: Harper. pp. 236. ISBN 0-06-041987-3.

- ^ Mittelman, Willard. "Maslow's Study of Self-Actualization - A Reinterpretation". Journal of Humanistic Psychology 31 (1): 114-135. doi: 10.1177/0022167891311010. http://jhp.sagepub.com/content/31/1/114.abstract. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ^ Motivation and Personality, Third Edition, Harper and Row Publishers

- ^ Bob F. Steere (1988). Becoming an effective classroom manager: a resource for teachers. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-88706-620-8, 9780887066207. http://books.google.com/?id=S2cwd56VvOMC&pg=PA21&dq=Maslow's+hierarchy+of+needs&cd=3#v=onepage&q=Maslow's%20hierarchy%20of%20needs.

- ^ Goble, F. The Third Force: The Psychology of Abraham Maslow. Richmond, Ca: Maurice Bassett Publishing, 1970. Pg. 62.

- ^ Maslow, Abraham. Motivation and personality. Harper and Row New York, New York 1954 ch. 4

- ^ Maslow, Abraham. Motivation and personality. Harper and Row New York, New York 1954 pg 91

- ^ Maslow, Abraham. Motivation and personality. Harper and Row New York, New York 1954 pg 92

- ^ Maslow, Abraham. Motivation and personality. Harper and Row New York, New York 1954 pg 93

- ^ Wikia

- ^ Cloninger, C.R.; Svrakic, DM; Przybeck, TR (December 1993). "A psychobiological model of temperament and character". Archives of General Psychiatry 50 (12): 975–90. DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008. PMID 8250684.

- ^ The Atlantic, Maslow 2.0: A New and Improved Recipe for Happiness

- ^ Tay, Louis; Diener, Ed (2011). "Needs and Subjective Well-Being Around the World". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101 (2): 354–365. http://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/psp-101-2-354.pdf. Retrieved Sept. 20, 2011.

- ^ Maslow 2.0 Human Hierarchy of Needs, Maslow 2.0: Human Hierarchy of Needs

- ^ Wahba, Mahmoud A.; Lawrence G. Bridwell (1974-09-27). "Maslow reconsidered: A review of research on the need hierarchy theory". Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 15 (2): 212–240. DOI:10.1016/0030-5073(76)90038-6. "The uncritical acceptance of Maslow's need hierarchy theory despite the lack of empirical evidence is discussed and the need for a review of recent empirical evidence is emphasized."

- ^ Hofstede, G (1984). "The cultural relativity of the quality of life concept". Academy of Management Review 9 (3): 389–398. DOI:10.2307/258280. JSTOR 258280. http://www.nyegaards.com/yansafiles/Geert%20Hofstede%20cultural%20attitudes.pdf.

- ^ Cianci, R., Gambrel, P.A. (2003). Maslow's hierarchy of needs: Does it apply in a collectivist culture. Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 143-161.

- ^ Maslow, Abraham. Motivation and personality. Harper and Row New York, New York 1954 ch. 4

- ^ Kenrick, D. (2010, May 19). Rebuilding Maslow’s pyramid on an evolutionary foundation. Psychology Today: Health, Help, Happiness + Find a Therapist. Retrieved July 16, 2010, from http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/sex-murder-and-the-meaning-life/201005/rebuilding-maslow-s-pyramid-evolutionary-foundation

- ^ Kenrick, D.T., Griskevicius, V., Neuberg, S.L., & Schaller, M. (2010). Renovating the pyramid of needs: Contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5. Retrieved July 16, 2010, from http://www.csom.umn.edu/assets/144040.pdf

- ^ Tang, T. L. P., & West, W. B. 1997. The importance of human needs during peacetime, retrospective peacetime, and the Persian Gulf War. International Journal of Stress Management, 4 (1): 47-62.

- ^ Tang, T. L. P., & Ibrahim, A. H. S. 1998. Importance of human needs during retrospective peacetime and the Persian Gulf War: Mid-eastern employees. International Journal of Stress Management, 5 (1): 25-37. http://www.springerlink.com/content/h1q9vg84760uhh5u/

- ^ Tang, T. L. P., Ibrahim, A. H. S., & West, W. B. 2002. Effects of war-related stress on the satisfaction of human needs: The United States and the Middle East. International Journal of Management Theory and Practices, 3 (1): 35-53.

External links

- A Theory of Human Motivation, original 1943 article by Maslow.

- Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, Teacher's Toolbox. A video overview of Maslow's work by Geoff Petty.

- A Theory of Human Motivation: Annotated.

- Theory and biography including detailed description and examples of self-actualizers.

- Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, Valdosta.

- Abraham Maslow by C George Boheree